DiceCTF: diceisyou

dice-is-you (RE):

This was a fun and interesting challenge which required reverse engineering webassembly, something I haven’t gotten the chance to do thus far.

hgarrereyn

19 solves / 251 points

DICE IS YOU

Controls:

wasd/arrows: movement

space: advance a tick without moving

q: quit to main menu

r: restart current level

z: undo a move (only works for past 256 moves and super buggy)

dice-is-you.dicec.tf

Initial Inspection

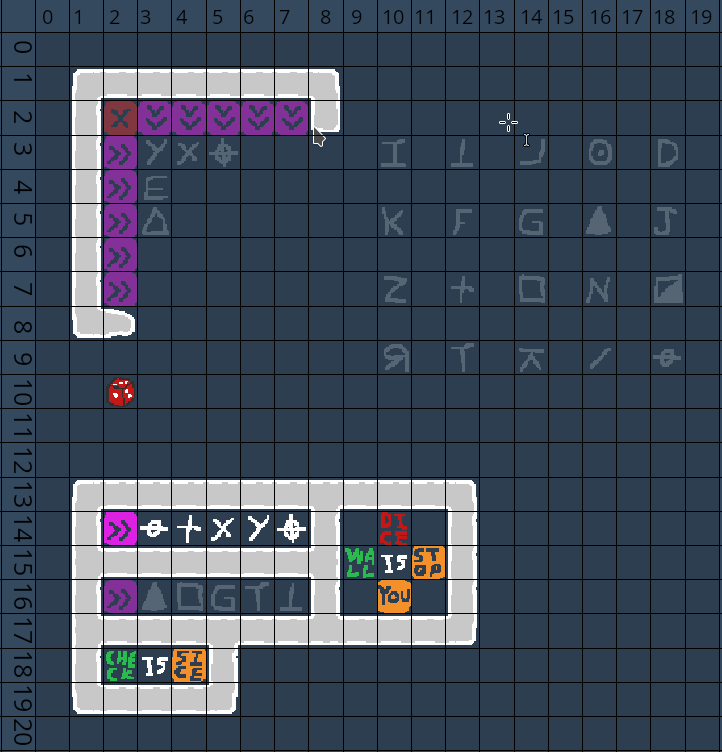

Despite being a RE challenge, this one comes with just a link to a website. If we go to that website we are greeted with a game board enabled by javascript.

The game is a “babaisyou” clone. The basic premise is that you have to reprogram the rules of the game in order to succeed. Winning the game means getting the character “you” on the object representing “sice” (NoVA slang for win/good).

Unfortunately, the interesting game mechanics have very little to do with the actual CTF.

You can watch me quickly solve the first 4 levels in the gif below.

After completing the first four levels, you will be faced with the final level which contains the real CTF problem.

Upon first inspection, the problem looks like it contains some sort of cryptography pattern stuff.

The bottom left portion of the game screen shows the main mechanic that we are working with. If you place 5 shapes in a specific order, the purple block will light up. This makes me expect that we need to place all 25 shapes in a specific 5 by 5 pattern so that all of the purple blocks in the upper left grid pattern will light up, hopefully granting a flag.

I always like to double check brute force feasibility for something like this. Why bother reverse engineering a lock if you can just rake it? Let’s see what our chances are of just guessing the pattern. We’ll give the author the benefit of the doubt that there is only ONE possible pattern which lights up all the purple blocks at once. Since the author has done us the favor of pre-placing 5 blocks, that means we’re looking for 1 pattern in 20! options.

nPr = 20! / (20-20)! = 2,432,902,008,176,640,000 possible permutations.

Looks like bruteforce is out of the question if we want this done in a reasonable amount of time.

With that being the case, we need to understand the logic behind what is causing the purple blocks to light up, and we need to know how each symbol is represented within that logic.

To do this, its time to snoop around on the webpage to see what is actually going on.

Planning the Path Forward

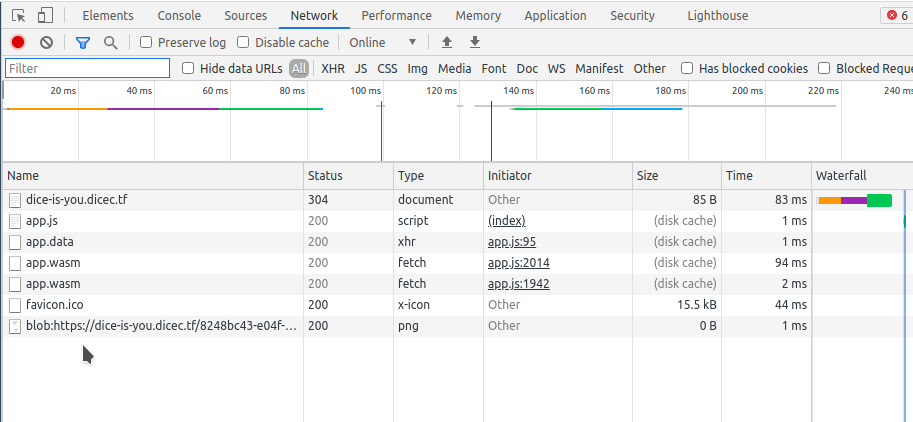

We can check what files are actually being served by the website in chrome, and it turns out that we’re getting served up a javascript file and a webassembly file. A quick look through the javascript file shows that nothing in there has anything to do with the game logic itself, so that leaves the webassembly file. We can download the .wasm using chrome, and then look around at what tools are available for helping us to reverse engineer it.

From googling around it looks like there are a few tools which could potentially help us with this task.

-

https://www.pnfsoftware.com/jeb/demowasm (JEB has a web assembly decompiler apparently)

-

https://github.com/WebAssembly/wabt (Toolsuite for working with webassembly binaries, has a decompiler to a “human readable” language, and can output unoptimizied c soure code)

- https://github.com/andr3colonel/ghidra_wasm (Looks like someone wrote a web assembly module for ghidra)

- We have chromes built in debugger which lets us debug the running program with breakpoints, watchpoints, and a memory view.

Upon looking at JEB, it turns out they want $1,800 dollars for a license. No thanks.

The ghidra module looks interesting, but I haven’t actually used ghidra modules before and didn’t really feel like fighting Ghidra’s inner workings during this CTF

That leaves us with two options.

wabtdecompilation combined with chrome’s debugger.

or

wabt’s c source code generator, recompile the program in x86, and THEN put it in ghidra.

I spent a small bit of time trying to recompile the c output but ended up not feeling like dealing with trying to fix the c code to a point where I could get it to recompile. This led me to just go ahead use wabt’s decompiler combined with chrome debugging.

The two of these tools combined should be more than enough for us to get a half-decent understanding of whats going on here.

Starting the analysis

Instructions for compiling wabt’s toolset can be found on their github. I think its also just available in the ubuntu apt repositories.

https://github.com/WebAssembly/wabt

The following command gets us some decompiled output.

wasm-decompile app.wasm > diceisyou.dcmp

Lucky for us the author left some symbols in the binary, so we get free function names to assist us.

function get_tile_pos_custom(a:{ a:int, b:int, c:int, d:int }, b:int, c:int, d:int, e:int) {

var w:int;

var f:int = stack_base;

var g:int = 48;

var h:int_ptr = f - g;

var i:int = 560;

var j:int = 760;

...

Lets look around for some key functions that we might care about:

menu_level()level1()level2()level3()level4()level_flag_fin()

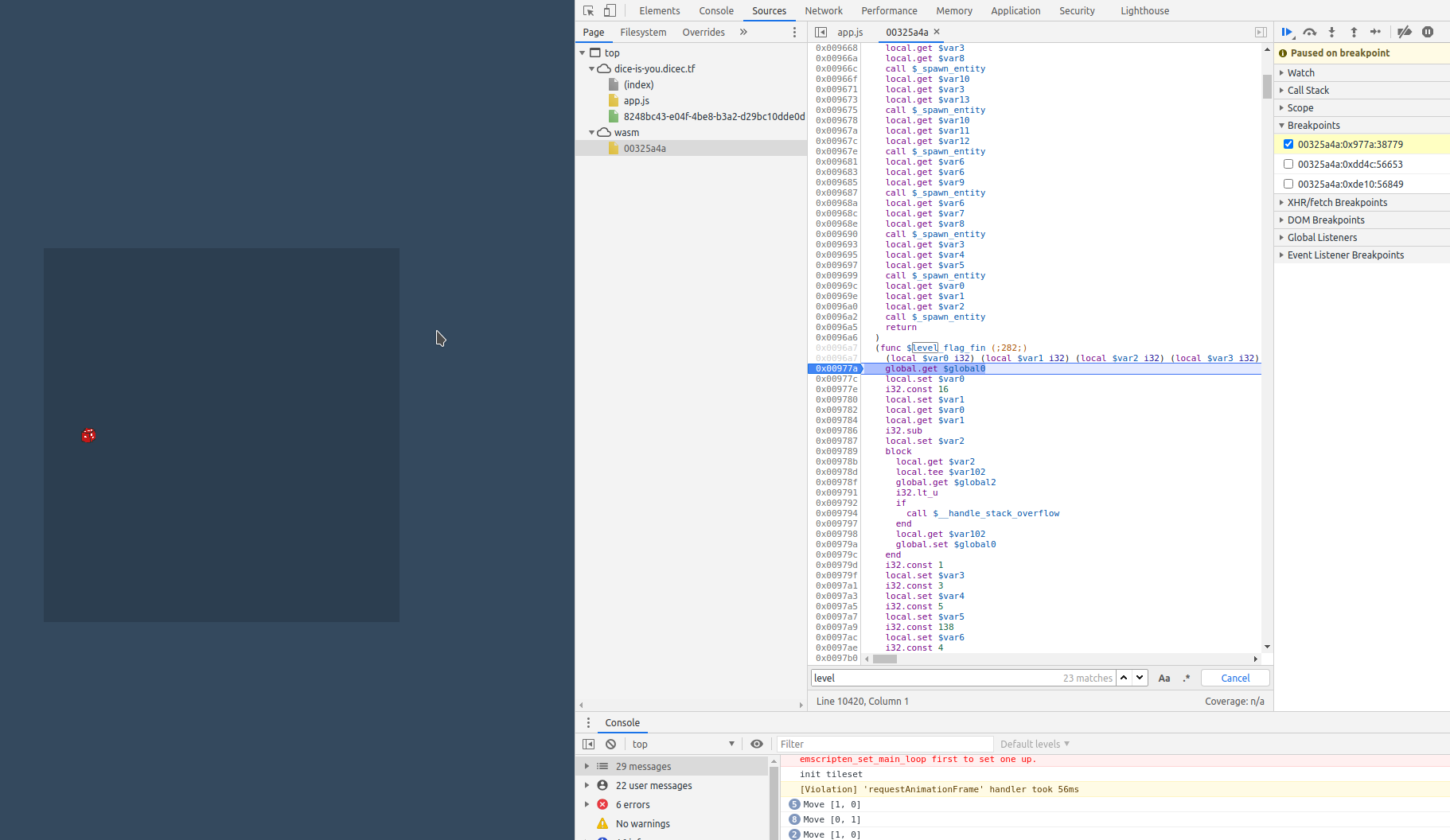

These seem to be initialization functions for the menu and each of the 5 levels. We can test this theory using the chrome debugger.

Confirmed. We get an execution pause right at the beginning of entry into the 5th level when we set a breakpoint at the beginning of level_flag_fin()

Let’s look a little more in depth at whats occurring to initialize the levels.

function level_flag_fin() {

var a:int = g_a;

var b:int = 16;

var c:int_ptr = a - b;

var yc:int = c;

if (yc < g_c) { handle_stack_overflow() }

g_a = yc;

label B_a:

var d:int = 1;

var e:int = 3;

var f:int = 5;

var g:int = 138;

var h:int = 4;

var i:int = 264;

var j:int = 198;

var k:int = 324;

var l:int = 330;

var m:int = 2;

var n:int = 8;

var o:int = -2;

var p:int = 7;

var q:int = 6;

var r:int = 342;

spawn_entity(m, m, r);

spawn_entity(d, d, o);

spawn_entity(m, d, o);

spawn_entity(e, d, o);

spawn_entity(h, d, o);

spawn_entity(f, d, o);

spawn_entity(q, d, o);

spawn_entity(p, d, o);

spawn_entity(n, d, o);

spawn_entity(n, m, o);

spawn_entity(d, m, o);

spawn_entity(d, e, o);

spawn_entity(d, h, o);

spawn_entity(d, f, o);

spawn_entity(d, q, o);

spawn_entity(d, p, o);

spawn_entity(d, n, o);

spawn_entity(m, n, o);

spawn_entity(e, e, l);

spawn_entity(h, e, k);

spawn_entity(f, e, j);

spawn_entity(e, h, i);

spawn_entity(e, f, g);

c[3] = d;

loop L_d {

var s:int = 12;

var t:int = c[3];

var u:int = t;

var v:int = s;

var w:int = u <= v;

var x:int = 1;

var y:int = w & x;

if (eqz(y)) goto B_c;

var z:int = 8;

var aa:int = 17;

var ba:int = -2;

var ca:int = 13;

var da:int = c[3];

spawn_entity(da, ca, ba);

var ea:int = c[3];

spawn_entity(ea, aa, ba);

var fa:int = c[3];

var ga:int = fa;

var ha:int = z;

var ia:int = ga <= ha;

var ja:int = 1;

var ka:int = ia & ja;

if (eqz(ka)) goto B_e;

var la:int = 15;

var ma:int = -2;

var na:int = c[3];

spawn_entity(na, la, ma);

label B_e:

var oa:int = 5;

var pa:int = c[3];

var qa:int = pa;

var ra:int = oa;

var sa:int = qa <= ra;

var ta:int = 1;

var ua:int = sa & ta;

if (eqz(ua)) goto B_f;

var va:int = 19;

var wa:int = -2;

var xa:int = c[3];

spawn_entity(xa, va, wa);

label B_f:

var ya:int = c[3];

var za:int = 1;

var ab:int = ya + za;

c[3] = ab;

continue L_d;

unreachable;

...

Taking a look at this code, the number of spawn_entity() function calls is pretty hefty. Just from its name, it seems like it is probably the function responsible for populating the board with the sprites. To confirm this, lets fill in a couple of the arguments, and see if we notice a pattern with the game board.

spawn_entity(1, 1, -2);

spawn_entity(2, 1, -2);

spawn_entity(3, 1, -2);

spawn_entity(4, 1, -2);

spawn_entity(5, 1, -2);

spawn_entity(6, 1, -2);

spawn_entity(7, 1, -2);

spawn_entity(8, 1, -2);

spawn_entity(8, 2, -2);

spawn_entity(1, 2, -2);

spawn_entity(1, 3, -2);

spawn_entity(1, 4, -2);

spawn_entity(1, 5, -2);

spawn_entity(1, 6, -2);

spawn_entity(1, 7, -2);

spawn_entity(1, 8, -2);

spawn_entity(2, 8, -2);

Here we notice that the arguments are following a pretty particular pattern. The third argument is always -2, and the other arguments seem to be incrementing 1 at a time in almost a for loop fashion.

In a grid based game board like this, its pretty much guaranteed that the sprites need to be populated using a coordinate system. This code is probably spawning a particular block, and I’d guess that its the wall sprite just because its the only block that appears this many times.

Lets double check that this makes sense:

Looks correct. If you treat the first and second argument of each of the above calls as coordinates, all of them would line up perfectly with the locations of the wall sprites in the top left sector. From this, we can almost surely tell that spawn_entity() follows the following function prototype:

spawn_entity(x_coord, y_coord, block_type)

We can combine the knowledge of our spawn_entity() calls, and our coordinate map, to ID every sprite type on the map and figure out what number represents each of them. We know this information will at least be useful since we know that the game logic for the purple blocks has to take into account which blocks are in a row to consider the row ‘correct’.

After an annoying amount of using find and replace in vscode, we can fill in the values for the next giant block of spawn_entity calls that we find in level_flag_fin()

spawn_entity(1, 14, -2);

spawn_entity(1, 16, -2);

spawn_entity(1, 18, -2);

spawn_entity(8, 14, -2);

spawn_entity(8, 16, -2);

spawn_entity(5, 18, -2);

spawn_entity(12, 14, -2);

spawn_entity(12, oc, -2);

spawn_entity(12, 16, -2);

//correct row

spawn_entity(2, 14, 270);

spawn_entity(3, 14, 210);

spawn_entity(4, 14, 174);

spawn_entity(5, 14, 324);

spawn_entity(6, 14, 330);

spawn_entity(7, 14, 198);

//incorrect row

spawn_entity(2, 16, 270);

spawn_entity(3, 16, 300);

spawn_entity(4, 16, 186);

spawn_entity(5, 16, 348);

spawn_entity(6, 16, 234);

spawn_entity(7, 16, 276);

//logic blocks

spawn_entity(10, 14, 27);

spawn_entity(10, 15, 0);

spawn_entity(10, 16, 6);

spawn_entity(9, 15, 15);

spawn_entity(11, 15, 18);

spawn_entity(2, 18, 45);

spawn_entity(3, 18, 0);

spawn_entity(4, 18, 30);

//Top Row

spawn_entity(16, 3, 240);

spawn_entity(18, 3, 252);

spawn_entity(10, 3, 294);

spawn_entity(12, 3, 276);

spawn_entity(14, 3, 288);

// 2nd Top Row

spawn_entity(16, 5, 300);

spawn_entity(18, 5, 312);

spawn_entity(10, 5, 306);

spawn_entity(12, 5, 318);

spawn_entity(14, 5, 348);

// 3rd Top Row

spawn_entity(16, 7, 336);

spawn_entity(18, 7, 150);

spawn_entity(10, 7, 162);

spawn_entity(12, 7, 174);

spawn_entity(14, 7, 186);

// Bottom Row

spawn_entity(16, 9, 258);

spawn_entity(18, 9, 210);

spawn_entity(10, 9, 222);

spawn_entity(12, 9, 234);

spawn_entity(14, 9, 246);

//purple blocks

spawn_entity(2, 3, 270);

spawn_entity(2, 4, 270);

spawn_entity(2, 5, 270);

spawn_entity(2, 6, 270);

spawn_entity(2, 7, 270);

//purple blocks

spawn_entity(3, 2, 282);

spawn_entity(4, 2, 282);

spawn_entity(5, 2, 282);

spawn_entity(6, 2, 282);

spawn_entity(7, 2, 282);

spawn_entity(2, 10, 36);

This lets us form a nice list of all the decimal values for the symbols.

| Type | Value |

|---|---|

| 138 | Triangle Empty |

| 150 | Square Half-Filled |

| 162 | Z |

| 174 | + |

| 186 | Square Empty |

| 198 | Crosshair horiz and vert |

| 210 | crosshair horiz |

| 222 | R backwards |

| 234 | T |

| 240 | Circle w/ Dot |

| 246 | Sideways K |

| 252 | D |

| 258 | / |

| 264 | E |

| 276 | T Upsidedown |

| 288 | Backwards L |

| 294 | I |

| 300 | Triangle Solid |

| 306 | K |

| 312 | J |

| 318 | F |

| 324 | x |

| 330 | y |

| 336 | N |

| 348 | G |

As a side note, while checking out the debugger during all this, I realized chrome gave us a nice little png image that contains all the sprites.

When we look at this image, we realize that all those values we spent so much time checking could’ve potentiall just been deduced by looking at the position of the sprite in this image if you treat it as a 30x12 grid…. Oh well.

Knowing the values of the sprites is nice. Lets try and look for the logic which actually lights up the purple blocks when 5 symbols get placed in order next to them.

Searching through the decompilation some more, we find a couple functions with names that sound like the kind of behavior we are looking for:

check_code(a:int, b:int, c:int, d:int)get_code_value(a:int)code(a:int, b:int, c:int, d:int, e:int)flag_rules(a:int, b:int)

All these functions sound like they could be related to the 5 digit symbol codes that we have to generate.

Upon checking in the debugger, we can confirm that putting breakpoints on these functions only stops the program execution on the 5th level.

Some further inspection shows us that check_code() calls get_code_value() 5 times, before then passing 5 arguments to the code() function.

Lets take a look at the code function:

function code(a:int, b:int, c:int, d:int, e:int):int {

var f:int = g_a;

var g:int = 16;

var h:int = f - g;

h[15]:byte = a;

h[14]:byte = b;

h[13]:byte = c;

h[12]:byte = d;

h[11]:byte = e;

var i:int = h[15]:ubyte;

var j:int = 255;

var k:int = i & j;

var l:int = 42;

var m:int = k * l;

var n:int = h[14]:ubyte;

var o:int = 255;

var p:int = n & o;

var q:int = 1337;

var r:int = p * q;

var s:int = m + r;

var t:int = h[13]:ubyte;

var u:int = 255;

var v:int = t & u;

var w:int = s + v;

var x:int = h[13]:ubyte;

var y:int = 255;

var z:int = x & y;

var aa:int = h[12]:ubyte;

var ba:int = 255;

var ca:int = aa & ba;

var da:int = z ^ ca;

var ea:int = w + da;

var fa:int = h[11]:ubyte;

var ga:int = 255;

var ha:int = fa & ga;

var ia:int = 1;

var ja:int = ha << ia;

var ka:int = ea + ja;

var la:int = 255;

var ma:int = ka & la;

return ma;

}

Its not particularly nice to look at, but if you take the time to read through this code, you quickly find that its doing quite a few mathematical operations using 5 values that are passed to it. This is probably the key logic which dictates whether or not the blocks light up when you place 5 in order. The 5 arguments are probably the 5 block values that are being passed in.

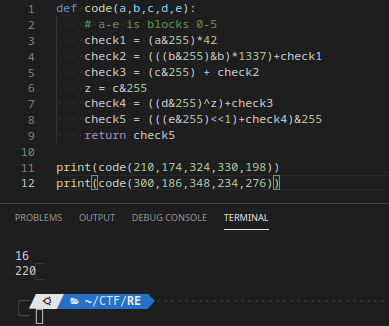

My teammate playoff-rondo decided to write this code in python to make it a little easier to read and execute if we needed.

def code(a,b,c,d,e):

# a-e is blocks 0-5

check1 = (a&255)*42

check2 = (((b&255)&b)*1337)+check1

check3 = (c&255) + check2

z = c&255

check4 = ((d&255)^z)+check3

check5 = (((e&255)<<1)+check4)&255

return check5When we run this code with the known working values and the non working values, the output didn’t seem to be anything in particular for the working case vs some false test cases.

Lets go back a little and see what happens in check_code() before get_code_value() gets called.

It seems that before the 5 values get sent to the code() function as inputs, they first pass through get_code_value().

function check_code(a:int, b:int, c:int, d:int):int {

var e:int = g_a;

var f:int = 32;

var g:int = e - f;

var dc:int = g;

if (dc < g_c) { handle_stack_overflow() }

g_a = dc;

label B_a:

g[6]:int = a;

g[5]:int = b;

g[4]:int = c;

g[3]:int = d;

var h:int_ptr = g[4]:int;

var i:int = h[0];

var j:int = get_code_value(i);

g[11]:byte = j;

var k:int_ptr = g[4]:int;

var l:int = k[1];

var m:int = get_code_value(l);

g[10]:byte = m;

var n:int_ptr = g[4]:int;

var o:int = n[2];

var p:int = get_code_value(o);

g[9]:byte = p;

var q:int_ptr = g[4]:int;

var r:int = q[3];

var s:int = get_code_value(r);

g[8]:byte = s;

var t:int_ptr = g[4]:int;

var u:int = t[4];

var v:int = get_code_value(u);

g[7]:byte = v;

var w:int = g[11]:ubyte;

var x:int = 255;

var y:int = w & x;

if (eqz(y)) goto B_e;

var z:int = g[10]:ubyte;

var aa:int = 255;

var ba:int = z & aa;

if (eqz(ba)) goto B_e;

var ca:int = g[9]:ubyte;

var da:int = 255;

var ea:int = ca & da;

if (eqz(ea)) goto B_e;

var fa:int = g[8]:ubyte;

var ga:int = 255;

var ha:int = fa & ga;

if (eqz(ha)) goto B_e;

var ia:int = g[7]:ubyte;

var ja:int = 255;

var ka:int = ia & ja;

if (ka) goto B_d;

label B_e:

var la:int = 0;

var ma:int = 1;

var na:int = la & ma;

g[31]:byte = na;

goto B_c;

label B_d:

var oa:int = g[11]:ubyte;

var pa:int = g[10]:ubyte;

var qa:int = g[9]:ubyte;

var ra:int = g[8]:ubyte;

var sa:int = g[7]:ubyte;

var ta:int = 255;

var ua:int = oa & ta;

var va:int = 255;

var wa:int = pa & va;

var xa:int = 255;

var ya:int = qa & xa;

var za:int = 255;

var ab:int = ra & za;

var bb:int = 255;

var cb:int = sa & bb;

var db:int = code(ua, wa, ya, ab, cb);

Let’s look at get_code_value() it a little closer:

function get_code_value(a:int):int {

var b:int = g_a;

var c:int = 16;

var d:int = b - c;

d[2]:int = a;

var e:int_ptr = d[2]:int;

var f:int = e[1];

var g:int = -138;

var h:int = f + g;

var i:int = 210;

h > i;

br_table[B_f, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_r, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_c, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_l, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_i, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_g, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_j, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_z, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_h, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_y, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_m, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_x, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_k, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_w, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_u, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_aa, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_q, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_t, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_o, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_p, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_v, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_e, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_d, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_n, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_b, B_s, ..B_b](

h)

label B_aa:

var j:int = 1;

d[15]:byte = j;

goto B_a;

label B_z:

var k:int = 5;

d[15]:byte = k;

goto B_a;

label B_y:

var l:int = 18;

d[15]:byte = l;

goto B_a;

label B_x:

var m:int = 25;

d[15]:byte = m;

goto B_a;

label B_w:

var n:int = 48;

d[15]:byte = n;

goto B_a;

label B_v:

var o:int = 49;

d[15]:byte = o;

goto B_a;

label B_u:

var p:int = 55;

d[15]:byte = p;

goto B_a;

label B_t:

var q:int = 61;

d[15]:byte = q;

goto B_a;

label B_s:

var r:int = 96;

d[15]:byte = r;

goto B_a;

label B_r:

var s:int = 119;

d[15]:byte = s;

goto B_a;

label B_q:

var t:int = 120;

d[15]:byte = t;

goto B_a;

label B_p:

var u:int = 135;

d[15]:byte = u;

goto B_a;

label B_o:

var v:int = 138;

d[15]:byte = v;

goto B_a;

label B_n:

var w:int = 148;

d[15]:byte = w;

goto B_a;

label B_m:

var x:int = 150;

d[15]:byte = x;

goto B_a;

label B_l:

var y:int = 160;

d[15]:byte = y;

goto B_a;

label B_k:

var z:int = 163;

d[15]:byte = z;

goto B_a;

label B_j:

var aa:int = 171;

d[15]:byte = aa;

goto B_a;

label B_i:

var ba:int = 179;

d[15]:byte = ba;

goto B_a;

label B_h:

var ca:int = 183;

d[15]:byte = ca;

goto B_a;

label B_g:

var da:int = 189;

d[15]:byte = da;

goto B_a;

label B_f:

var ea:int = 192;

d[15]:byte = ea;

goto B_a;

label B_e:

var fa:int = 194;

d[15]:byte = fa;

goto B_a;

label B_d:

var ga:int = 212;

d[15]:byte = ga;

goto B_a;

label B_c:

var ha:int = 247;

d[15]:byte = ha;

goto B_a;

label B_b:

var ia:int = 0;

d[15]:byte = ia;

label B_a:

var ja:int = d[15]:ubyte;

var ka:int = 255;

var la:int = ja & ka;

return la;

}

This function looks like its some sort of switch case statement table.

Upon further inspection, it is, though it individually accounts for every possible input value up to the max i of 210.

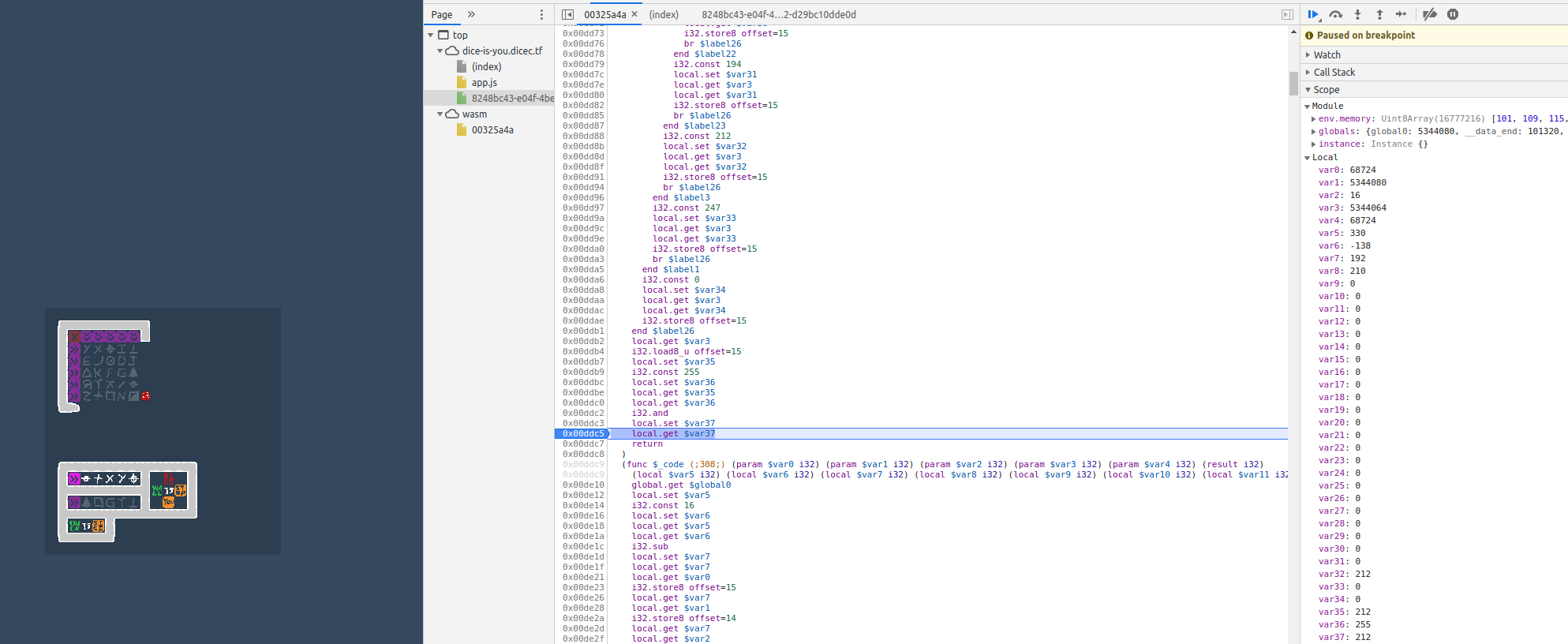

The function subtracts 138 from the input value (the sprite decimal values), then uses that value as an index to jump to whatever label is at that index in the br_table. This kind of sucks because it looks like the labels are ordered in the code based on the output value instead of in order of how they appear in the table.

I decided the laziest way to reverse this table was to just use the debugger. By placing the symbols all within the grid (even in the incorrect order) all the symbols should end up getting processed by this code so we can just set a breakpoint at the end of the table code in the debugger and look at what the function input was versus what the output was until we’ve recorded all the pairs.

In the below photo, all we have to do is look at var5 for the input value (var7 will be the value with 138 subtracted) and the output value will appear in var35. In this case, we can see that a 192 input, ends up with a value of 212 being returned.

This will take us a minute or two, but after 25 times, we should know all 25 translation pairs.

We record them (with the 138 subtracted off the original values) to the following table with the symbols written next to them for reference Conversion Table for get_code_value

0 -> 192 Triangle Empty

12 -> 119 Square Half filled

24 -> 247 Z

36 -> 160 Plus sign

48 -> 179 Square Empty

60 -> 189 crosshair hor and vert

72 -> 171 crosshair hor

84 -> 5 R backwards

96 -> 183 T

102 -> 18 Circle w/ Dot

108 -> 150 Sideways K

114 -> 25 D

120 -> 163 Backslash

126 -> 48 E

138 -> 55 T Upside Down

150 -> 1 L Backwards

156 -> 120 I

162 -> 61 Triangle Solid

168 -> 138 K

174 -> 135 J

180 -> 49 F

186 -> 194 x

192 -> 212 y

198 -> 148 N

210 -> 96 G

anything else -> 0

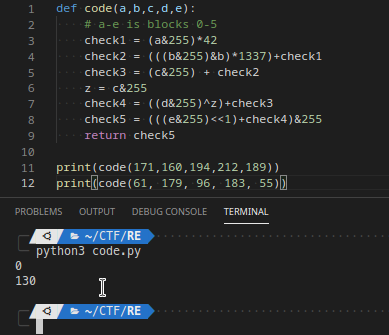

Knowing these now, let’s go back to our python code, and try to run it with the updated values.

This makes much more sense. For the working cases, the 5 numbers will cause code() to return zero after all the math is run on them.

We now know the constraints for creating a pattern where all 10 purple blocks will light up.

Finding the Solution

Unfortunately, knowing the constraints doesn’t mean we can just arrange the blocks properly. We have to be particular about where we place the blocks because each block has to be in the correct place TWICE. Once for each time it is in a pattern of 5 from the purple blocks. This means we can’t just guess and check or slowly build the patten up from the beginning because a pattern could be correct left/right, but its block positions can still break the up/down pattern.

This kind of problem needs to be solved be either intelligent recursion, or simply using a solver like z3 or angr.

z3 is the obviously more simple choice.

For those who don’t know what z3 is a software library which can solve programmatic systems of equations given a set of constraints. Its an EXTREMELY powerful tool which you should look into if you haven’t already. The dumbed down explanation is that, its a tool that you can give constraints and a desired output to, and it will solve for the input.

Z3 will allows us to feed it the code() function, the 25 possible input characters, the 5 known input character locations, and the constraints that code() must be true for each column and row, and will provide us with the appropriate input which will pass all our constraints.

I’m not a Z3 expert, and was too sleep deprived to read through the documentation at this point, so I took all this information and handed it off to my teammate playoff-rondo who is way more familiar with Z3 and went to sleep. He constructed this script, which properly solves the mathematical side.

from z3 import *

import IPython

s = Solver()

grid = []

#construct the grid

for x in range(5):

r = []

for y in range(5):

r.append(BitVec('x%iy%i'%(x,y),32))

grid.append(r)

#add the constraints for the author given symbol locations

s.add(grid[0][0] == 212)

s.add(grid[0][1] == 194)

s.add(grid[0][2] == 189)

s.add(grid[1][0] == 48)

s.add(grid[2][0] == 192)

def code(a,b,c,d,e):

# a-e is blocks 0-5

check1 = (a&255)*42

check2 = (((b&255)&b)*1337)+check1

check3 = (c&255) + check2

z = c&255

check4 = ((d&255)^z)+check3

check5 = (((e&255)<<1)+check4)&255

return check5

#list of symbols which can be used as input.

valid_nums= [192,119,247,160,179,189,171,5,183,18,150,25,163,48,55,1,120,61,138,135,49,194,212,148,96]

# constrain to valid

for x in range(5):

for y in range(5):

c = []

for n in valid_nums:

c.append(grid[x][y] == n)

s.add(Or(c))

#constrain that all rows must return 0 when run through code()

for row in grid:

s.add(code(row[0],row[1],row[2],row[3],row[4]) == 0)

#constrain that all columns must return 0 when run through code()

def column(matrix, i):

return [row[i] for row in matrix]

for x in range(5):

c = column(grid,x)

s.add(code(c[0],c[1],c[2],c[3],c[4]) == 0)

#constrain that all symbols must be unique (no repeats of the same symbol)

s.add(Distinct(sum(grid,[])))

# print board as a grid

if s.check():

m = s.model()

for x in grid:

for y in x:

print(str(m[y],).ljust(3," "),"|",end="")

print("\n"+"_"*25)

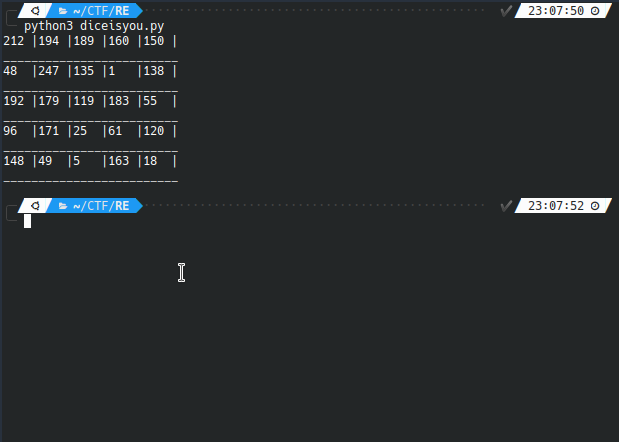

IPython.embed()This code outputs a grid containing the correct values.

Lets try this as input in the actual game!

Looks like that worked!

Flag:

dice{d1ce_1s_y0u_is_th0nk_73da6}

Great challenge!